Social Theory

This profound recognition provides material upon which to base social theory speculations about society and human existence.

As someone once said:-

It is better to light a candle than

to forever curse the darkness

Is "Human Being" more truly Metaphysical than Physical?

to forever curse the darkness

Is "Human Being" more truly Metaphysical than Physical?

A "Human Tripartism"?

In Philosophy "Metaphysics" is the branch of Philosophy dealing with "being": how things exist, what things really are, what essence is, what it is 'to be' something, etc.

The word comes from a "book" of some thirteen treatises written by Aristotle which were traditionally arranged, by scholars who lived in the centuries after Aristotle's life-time in the fourth century B.C., after those of his "books" which considered physics and natural science.

The principal subject of Aristotle's thirteen treatises is "being qua being", or being understood as being.

At the heart of the book lie three questions:-

What is existence, and what sorts of things exist in the world?

How can things continue to exist, and yet undergo the change we see about us in the natural world?

And how can this world be understood?

It may be that for want of other terminology directly suited to reference such elusive subject matter the term MetaPhysica, (in Greek it means "after physics" or "beyond physics"), was adopted in relation to Aristotle's "book" of "metaphysical" treatises.

The Tripartite Soul approach to insights into human nature can even be extended to a "Societal Level" of speculations about society and human existence.

"In old Rome the public roads beginning at the Forum

proceeded north, south, east, west, to the centre of every

province of the empire, making each market-town of Persia, Spain,

and Britain pervious to the soldiers of the capital: so out of

the human heart go, as it were, highways to the heart of every

object in nature, to reduce it under the dominion of man. A man

is a bundle of relations, a knot of roots, whose flower and

fruitage is the world. His faculties refer to natures out of him,

and predict the world he is to inhabit, as the fins of the fish

foreshow that water exists, or the wings of an eagle in the egg

presuppose air. He cannot live without a world."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

History (1841)

Ralph Waldo Emerson

History (1841)

This view suggests that Societies themselves!!! have a Tripartite character.

What is the business of history? What is the

stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage

of history? Man : evidently man and human

nature. There are many different elements in history. What are they?

Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the

development of humanity, and of humanity only;

for nothing else but humanity developes itself, for

nothing else than humanity is free. ...

... Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations.

Victor Cousin

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1832)

"Whatever concept one may hold, from a metaphysical point of view, concerning the freedom of the will, certainly its appearances, which are human actions, like every other natural event, are determined by universal laws. However obscure their causes, history, which is concerned with narrating these appearances, permits us to hope that if we attend to the play of freedom of the human will in the large, we may be able to discern a regular movement in it, and that what seems complex and chaotic in the single individual may be seen from the standpoint of the human race as a whole to be a steady and progressive though slow evolution of its original endowment."

Immanuel Kant

Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1784)

In his essay "History" Ralph Waldo Emerson sets out an

approach to History where the "innate Humanity"

that is common to all of mankind is seen as operating throughout

the ages in the shaping of events. The first two paragraphs

include such sentiments as:- ... Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations.

Victor Cousin

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1832)

"Whatever concept one may hold, from a metaphysical point of view, concerning the freedom of the will, certainly its appearances, which are human actions, like every other natural event, are determined by universal laws. However obscure their causes, history, which is concerned with narrating these appearances, permits us to hope that if we attend to the play of freedom of the human will in the large, we may be able to discern a regular movement in it, and that what seems complex and chaotic in the single individual may be seen from the standpoint of the human race as a whole to be a steady and progressive though slow evolution of its original endowment."

Immanuel Kant

Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1784)

"There is one mind common to all individual men.

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. All the facts of history pre-exist as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of this manifold spirit to the manifold world".

"History is for human self-knowledge ... the only clue to what man can do is what man has done. The value of history, then, is that it teaches us what man has done and thus what man is."

R. G. Collingwood

The study of history is the beginning of political wisdom.

Jean Bodin

Human Nature and the course of Human History

It could be suggested that long, long, ago Human Beings, each endowed with a glimmer of intelligence, typically lived in tribes and tribal kingdoms.

How far can it be accepted that in pre-historic times "Existentially Tripartite" behavioural forces, of the operation of which the Human Beings concerned were unaware, practically determined that almost everyone then living lived a tribe or a in tribal kingdom?

As time passed populations increased. Rudimentary technologies grew slightly more sophisticated. Trade in pottery, metals, oils, wines and grains began to be developed by sea and land. Tribes and tribal kingdoms tended to be peacefully absorbed by emergent neighbouring city-states which featured such things as civic adminstrators, standing armies and the rudiments of learning, laws and literatures AND where persons drawn from many tribes lived side by side with persons born within the city states in relatively sophisticated civilisational societies.

... you must take the whole society to find the whole man. Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state these functions

are parcelled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Small scale city-states and tribes and tribal kingdoms

themselves subsequently tended to be forcibly absorbed by burgeoning Empire's; such as that of Imperial Rome.Such absorption taking place through the availability of opportunities to more fully and securely participate in wide-spread trading networks, diplomatic pressures, offers of "protection after alliance", or actual conquest.

Empire's rise and empire's fall. Following on from the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Human Beings in southern and western Europe found themselves to be living in situations where a majority accustomed to living within the societal environments that had been maintained by the now fallen Empire were obliged to live under the political sway of such peoples as the Goths, Franks, Vandals and Lombards who had swept across the former imperial frontiers and established themselves as holders of power in various regions of the former Roman Empire.

These incomers were often somewhat disposed to respect some aspects of the civilisational heritage of Imperial Rome.

European societies tended to become organised feudally - that is to say Emperors and Kings were sovereign and looked to lesser lords, who held lands together with a workforce of vassal peasantry, for political support.

It has been said of such feudal times that "some men worked, some men fought and some men prayed" (Existential Tripartism in operation?).

The peasantry, artisans and merchants worked helping to create wealth so all could live, pay rents, royal taxes and church tithes whilst also having some hope of attaining some satisfactions in life through friendships, relationships, religious practices and such forms of secular entertainment as circumstances offered.

The lords fought - between themselves, for or against their sovereign and, from time to time, against their sovereign's dynastic rivals.

Feudal support by lesser lords of greater ones to whom they were held to owe "knight service" may have involved agreement about how many knights and men-at-arms maintained by the lesser lord could be placed at the greater lords service when required.

Churchmen and churchwomen prayed, maintained traditions of learning, provided charitable help to the poor, supported the rule of law and contributed to progressive agricultural practices.

People have a capacity for spirituality; rich and poor could find that their innate sensibility of divinity could relate positively to the ways in which young people were formally admitted into a community of believers through baptism, where marriages were celebrated under rituals performed by men of God and where those who died were interred with due observance of solemn rites.

Such was the sway of religion that massive landholdings were accumulated, stone-built cathedrals and churches were raised at monumental expense.

At times, in some parts of Europe, more than one-in-five of the adult population lived as priests or within monasteries and convents.

Emperors and Kings were personally sovereign over dynastic lands and over the inhabitants of those lands. Sovereignty could be inherited by those of "Royal Blood" or won in wars. The sons and daughters or royal houses were expected to enter into dynastic marriages which would help secure systems of alliance between dynastic states and in time open up preferred possibilities for the inheritance of dynastic sovereignty. Dynastic wars took place from time to time where rival monarchs contested their perceived right of inheritance of sovereignty over lands and peoples against other dynastic claimants.

Emperors and Kings came increasingly to hold personal, heritable, sovereignty over widespread lands upon which persons who communicated in diverse dialects lived but tended to maintain courts and adminstrations which were conversant in latin (initially) but increasingly in the dominant language of those Empires and Kingdoms as they tended to become somewhat "linguistically rooted".

Time moved on and brought about such changes as a growth in trade and population. Merchants and artisans tended from time to time to gain in prosperity and to be somewhat educated. Emperors and Kings could look to towns and cities as sources of taxation and, in times of challenge to their authority, could even look to towns and cities as sources of political support against sometimes turbulent nobles and sometimes domineering churchmen.

In 1862, Lord Acton who was then a leading historian, wrote one of his more influential essays entitled ~ Nationality ~ which contains the following

passage:-

... In the old European system, the rights of nationalities were neither recognised by governments nor asserted by the people. The interest of the reigning families, not those of the nations, regulated the frontiers; and the administration was conducted generally without any reference to popular desires. Where all liberties were suppressed, the claims of national independence were necessarily ignored, and a princess, in the words of Fénelon, carried a monarchy in her wedding portion. The eighteenth century acquiesced in this oblivion of corporate rights on the Continent, for the absolutists cared only for the State, and the liberals only for the individual. The Church, the nobles, and the nation had no place in the popular theories of the age; and they devised none in their own defence, for they were not openly attacked. The aristocracy retained its privileges, and the Church her property; and the dynastic interest, which overruled the natural inclination of the nations and destroyed their independence, nevertheless maintained their integrity ...

In 1879 Edward Augustus Freeman, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University, wrote:-

... A hundred years ago man's political likes and dislikes seldom went beyond the range suggested by the place of his birth or immediate descent, Such birth or descent made him a member of this or that political community, a subject of this or that prince, a citizen - perhaps a subject - of this or that commonwealth. The political community of which he was a member had its traditional alliances and traditional enemies, and by those traditional alliances and traditional enemies the likes and dislikes of the members of that community were guided. But those traditional alliances and enemies were seldom determined by theories about language or race. The people of this or that place might be discontented under a foreign government; but, as a rule, they were discontented only if subjection to that foreign government brought with it personal supression or at least political degradation. Regard or disregard of some purely local priviledge or local feeling went for more than the fact of a government being native or foreign. What we now call the sentiment of nationality did not go for much; what we call the sentiment of race went for nothing at all ...

... In the old European system, the rights of nationalities were neither recognised by governments nor asserted by the people. The interest of the reigning families, not those of the nations, regulated the frontiers; and the administration was conducted generally without any reference to popular desires. Where all liberties were suppressed, the claims of national independence were necessarily ignored, and a princess, in the words of Fénelon, carried a monarchy in her wedding portion. The eighteenth century acquiesced in this oblivion of corporate rights on the Continent, for the absolutists cared only for the State, and the liberals only for the individual. The Church, the nobles, and the nation had no place in the popular theories of the age; and they devised none in their own defence, for they were not openly attacked. The aristocracy retained its privileges, and the Church her property; and the dynastic interest, which overruled the natural inclination of the nations and destroyed their independence, nevertheless maintained their integrity ...

In 1879 Edward Augustus Freeman, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University, wrote:-

... A hundred years ago man's political likes and dislikes seldom went beyond the range suggested by the place of his birth or immediate descent, Such birth or descent made him a member of this or that political community, a subject of this or that prince, a citizen - perhaps a subject - of this or that commonwealth. The political community of which he was a member had its traditional alliances and traditional enemies, and by those traditional alliances and traditional enemies the likes and dislikes of the members of that community were guided. But those traditional alliances and enemies were seldom determined by theories about language or race. The people of this or that place might be discontented under a foreign government; but, as a rule, they were discontented only if subjection to that foreign government brought with it personal supression or at least political degradation. Regard or disregard of some purely local priviledge or local feeling went for more than the fact of a government being native or foreign. What we now call the sentiment of nationality did not go for much; what we call the sentiment of race went for nothing at all ...

An outline of earlier Europe history having been presented we can now begin to move to more explicitly consider whether an

acceptance and appreciation of the Existential Tripartism to

Human Nature, as suggested by the Major World Religions, by Plato and Socrates, and by Shakespeare (and by other authorities!!!)

as related on Our Spirituality & the Wider World page

seems to provide a reliable foundation for the development of further Key Wisdoms about

ourselves as complex "Human" Beings, about the "Human" Societies we have developed and

which we inhabit and about

why "Human" History has featured certain turbulent episodes.

Following on from a little more "setting of the scene" making very brief mention of the American Revolution of circa 1772-1783, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic turmoils of 1789-1815 and a rather less brief mention of the European Revolutions of 1848 our pages can then be turned towards a consideration of Modern European History ~ including detailed coverage of the following transformational, and highly instructive, episodes:-

Following on from a little more "setting of the scene" making very brief mention of the American Revolution of circa 1772-1783, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic turmoils of 1789-1815 and a rather less brief mention of the European Revolutions of 1848 our pages can then be turned towards a consideration of Modern European History ~ including detailed coverage of the following transformational, and highly instructive, episodes:-

Popular European History pages on this site

The European Revolutions of 1848

Italian Unification - Cavour, Garibaldi and the Unification of Risorgimento Italy

Otto von Bismarck & The wars of German unification

First World War ~ Diplomacy : The ideas of Woodrow Wilson and Lenin

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, (wherein thirteen "British" colonial entities

on the eastern seaboard of the North American continent were replaced by the establishment of a confederation to be known

as the United States of America), and the changes in perspectives and

expectations about the permanence, or otherwise, of monarchical sovereignty and of the attainability of constitutional liberties that that revolution had helped to set in train

there were far-reaching developments in Europe.

Italian Unification - Cavour, Garibaldi and the Unification of Risorgimento Italy

Otto von Bismarck & The wars of German unification

First World War ~ Diplomacy : The ideas of Woodrow Wilson and Lenin

The French king had authorised a quite extensive French financial and military participation in that conflict which had helped to bankrupt his realm and which had led to some enthusiasm amongst sections of the French population for the forms of Constitutional liberty that those who, in the historical circumstances of the day, had taken it upon themselves to act as "American patriots" had sought from the British crown.

George Washington served two terms as the first holder of presidential office in the United States.

Throughout these years portraits of King Louis IV of France, and of his wife Marie-Antoinette, were prominently on view in the presidential reception rooms. King Louis' birthday was also marked by a public holiday in the U.S.

The American War of Independence did much to set the stage for the French Revolution of 1789.Throughout these years portraits of King Louis IV of France, and of his wife Marie-Antoinette, were prominently on view in the presidential reception rooms. King Louis' birthday was also marked by a public holiday in the U.S.

The finances of the French crown had been drained by the diverse negative outcomes of several years of appallingly bad weather, by disadvantageous trade policies adopted by the king as well as by involvement in the American War of Independence.

The depth and seriousness of the financial crisis led to the convening of an historic, but somewhat lapsed, consultative body called the Estates General which had actually not been called upon to hold sessions since 1614.

If things had proceeded as the French king intended, an outcome would have been produced where, following the precedents of earlier Estates General, a "First Estate" of churchmen, a "Second Estate" of noblemen, and a "Third Estate" of the bulk of the population, deliberating as three separate "Orders" (Existential Tripartism in operation?) would have found ways of complying with the king's policy aspirations.

In the circumstances of 1789 this principally would have meant meeting the necessity of raising extra finances for the Royal treasury.

The Estates General first convened at Versailles on 5 May, 1789, after lavish ceremonials where the representatives of the Three Orders had gathered together wearing their diverse dress of rank.

Things did not, however, work out as the King of France hoped.

Prior to the actual calling together of the Estates General a prominent Royal minister named Necker had asked for opinions as to its Constitution.

It was in response to this that the Abbé Sieyès penned his pamphlet Qu'est-ce que le tiers état? ( What is the third estate? ).

This pamphlet, published in early 1789, attacked noble and clerical privileges and was hugely popular throughout France amongst the many persons who hoped for reform.

Abbé Sieyès' pamphlet begins:-

The plan of this book is fairly simple. We must ask ourselves three questions.

1. What is the Third State? Everything.

2. What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing.

3. What does it want to be? Something....

and ends:-

The Third Estate embraces then all that which belongs to the nation; and all that which is not the Third Estate, cannot be regarded as being of the nation.

What is the Third Estate?

It is everything.

Abbé Sieyès was elected as one of the Third Estate deputies from Paris to the Estates General of 1789 and became known of as advocating the abandonment of the traditional functioning of the Estates General as three Estates deliberating as seperate blocs each of which had a separate right to offer, or to withold, consent and advocated the formation of a single chamber National Assembly.

Thus, even before the Estates General actually held its earliest opening sessions vocal "Third Estate" representatives were making it plain that they wished for voting to take place in a National Assembly par tete (by head) rather for deliberations to take place par ordre (by each order separately) amidst a climate where the sovereignty of the people or national sovereignty, and constitutional governance were seen, by many intellectual Third Estate representatives, by liberal public opinion, and by some churchmen, as being legitimate demands.

Almost as soon as the Estates General began to hold procedural sessions transformations began to occur where a clear majority of the Third Estate delegates were voluntarily joined by a limited but increasing number of delegates drawn from the clericalist "Second Estate" in the unauthorised establishment of a would-be National Assembly.

Events seemed to be moving towards the establishment of a form of constitutional monarchy but began to take on a more serious and somewhat revolutionary tone with the storming and capture, by sections of the Parisian population, of a royal fortress known as the Bastille on July 14, 1789.

Power soon fell to democratising and otherwise reforming interests in France who, alongside pursuing political and social change in France also thought it appropriate to send a key of the Bastille to the American president George Washington in recognition of the power of the recent American revolutionary example to provide inspiration for their own efforts at securing liberties in France.

The French Revolution of 1789, and the Napoleonic era which followed it until 1815, both brought further changes in Human perspectives and expectations about the roles of God and Religion in the world, about the sovereignty of Emperors and Kings and about the sovereignty of Peoples as an alternative, about constitutions, liberty and democracy, about nations and nationality and about the just ordering of society.

Europe actually looked like this as recently as 1815!!!

(This outcome having been agreed at a "European / Monarchical"

"Congress of Vienna" following the defeat of Napoleon!)

Napoleon called a new power into existence by attacking nationality in Russia, by delivering it in Italy, by governing in defiance of it in Germany and Spain. The sovereigns

of these countries were deposed or degraded; and a system of administration was introduced which was French in its origin, its spirit, and its instruments. The people resisted

the change. The movement against it was popular and spontaneous, because the rulers were absent or helpless; and it was national, because it was directed against foreign

institutions. In Tyrol, in Spain, and afterwards in Prussia, the people did not receive the impulse from the government, but undertook of their own accord to cast out the

armies and the ideas of revolutionised France. Men were made conscious of the national element of the revolution by its conquests, not in its rise. The three things which

the Empire most openly oppressed - religion, national independence, and political liberty - united in a short-lived league to animate the great uprising by which

Napoleon fell. Under the influence of that memorable alliance a political spirit was called forth on the Continent, which clung to freedom and abhorred revolution,

and sought to restore, to develop, and to reform the decayed national institutions.

Lord Acton ~ Nationality

Individual Human Beings in various parts of Europe, the literate and relatively prosperous initially but wider

society thereafter, were often no longer content to see themselves as being under the authoritative rule of this

or that dynasty but increasingly expected that they should have an extensive say in how they were governed.

Lord Acton ~ Nationality

To some degree dynastic sovereignty was being rejected, in various parts of Europe, by "the spirit of the age" and popular / national sovereignty was becoming accepted in its place. Human desires for more meaningful and enhanced modes of existence tended, initially amongst relatively prosperous and intellectually engaged sections of the populations of various dynastic states but more widely thereafter, to become fascinated by romanticisations of nationality and of the nationhood with which individuals could personally self-identify.

Empires and kingdoms were often historically sovereign over many linguistic groups.

Given such circumstances fascination with, and romanticisation of, nationality and nationhood began to allow sections of many historic dynastic states' populations to see themselves as personally being members of culturally or linguistically suppressed minorities rather than as members of this or that broader political community, or as subjects of this or that prince, or as citizens - or subjects - of this or that commonwealth.

The populations of the historic states of Europe, most of whom had been living fairly acceptingly of the then prevailing social order, now found themselves to be living in a world of increasingly evidently contesting ideas where religion, monarchy, constitutionalism, liberalism, democracy, nationalism and socialism all had their supporters.

The previously long-established Dynastic Europe of sovereign Emperors and Kings, and priviledged aristocracies and churchmen, found itself to be faced with potent challenges from such ideas as constitutional liberalism, democracy and nationalism.

During widespread European Revolutions of 1848 constitutional and liberalising demands were initially made by peoples of their rulers.

The ancient sovereignty of the Habsburgs, which held dynastic sway over markedly linguistically diverse territories, (largely due to fortuitous dynastic marriages and resulting inheritances of sovereignty over previous centuries), was seen as being on the point of being overthrown.

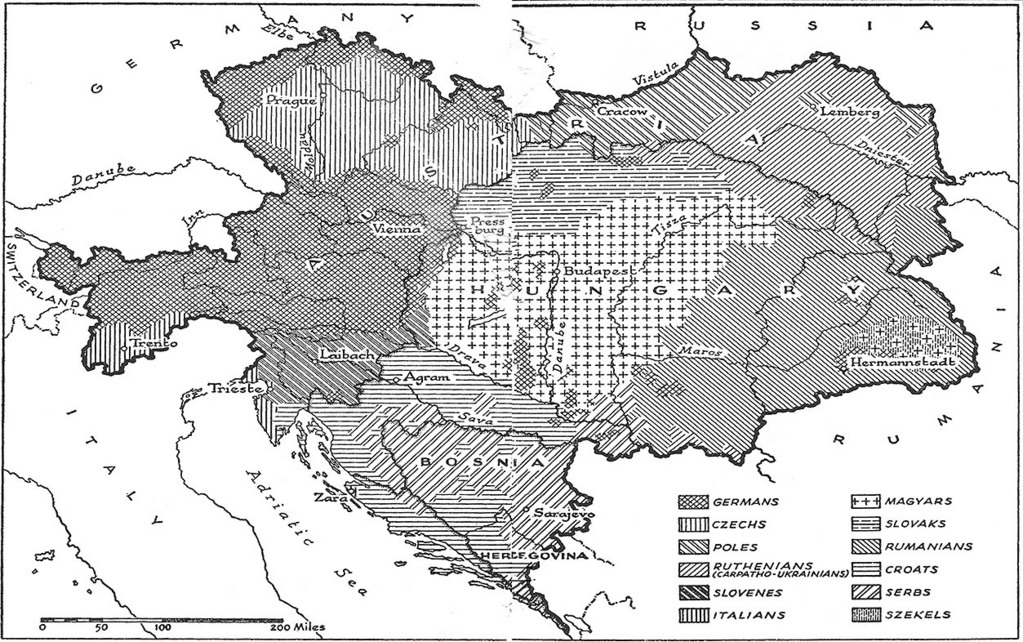

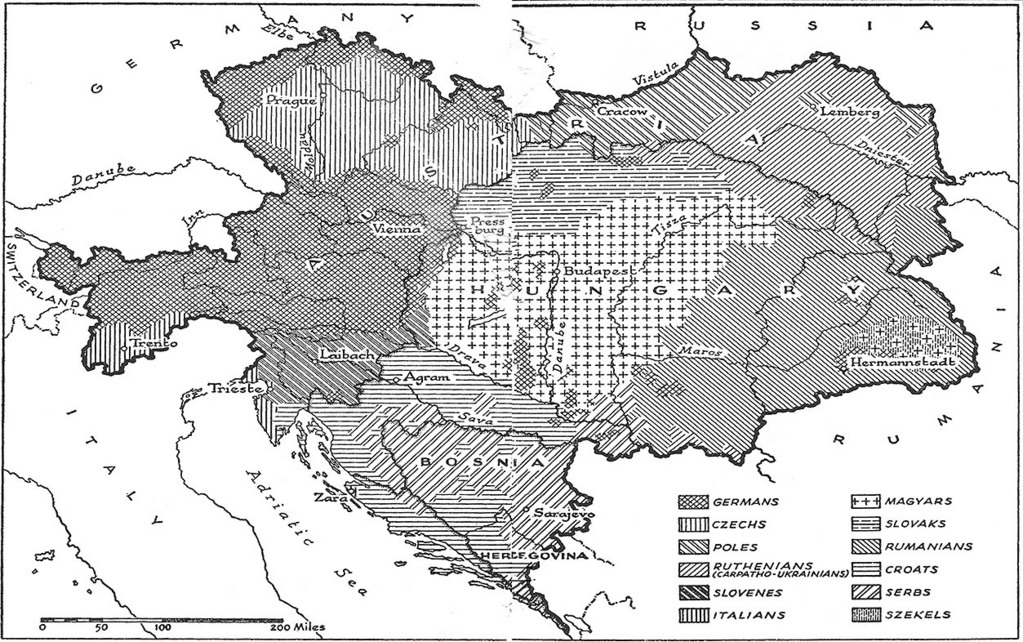

This outline map of the Habsburg Monarchy's truly immense territories shows

how they lay both within and (to the east) outside the

(N.B. Lombardy and Venetia to the south of the Tyrol,

in the Italian Peninsula, were also under Habsburg sovereignty)

Peoples of the Habsburg Monarchy / Austrian Empire

As events unfolded the Habsburg Monarchy became split between its more "historically Austrian" aspect and its more "historically Hungarian or Magyar" aspect.

Subsequent developments proceeded differently in each of these aspects as those at the centre of events within each actually pursued divergent policies in attempting to lay down political, administrative and linguistic foundations for their respective futures.

The Hungarian kingdom had long functioned under Habsburg sovereignty, (after a particularly historically momentous dynastic inheritance!), with the assistance of a largely consultative assembly known as the Hungarian Diet. In the heady days of the onset of the revolutionary turmoils in early March, 1848, members of this Diet sought to establish independences for the Hungarian kingdom. They intended that the Hungarian kingdom remain under the sovereignty of the Habsburg ruler but as a constitutional and distinct Kingdom of Hungary, rather than as an indistinct and politically impotent region of a wider system of absolutist monarchy.

Within this would-be constitutional Kingdom of Hungary a traditionally relatively powerful Hungarian-Magyar minority existed, (some 40% of the overall population), and showed evidences of wishing to be linguistically predominant such that deep divisions tended to emerge, between human groups conscious, or newly becoming conscious, of being members of this or that ethnic or linguistic group or nation.

Romanians, Croats, Serbs and Slovaks all began to offer determined opposition to the politically and linguistically centralising policies favoured by the Magyar dominated Diet of the Hungarian kingdom.

Those who were living within those territories associable with the Kingdom of Hungary had previously lived peaceably side-by-side amidst something of a patchwork of the historic settlement of populations. These lands had previously been administered, and represented at the Hungarian diet, through the Latin language which the sons of all relatively priviledged families tended to have opportunities to thoroughly learn, regardless of communal or confessional background, during youthful years spent receiving a then standard "classical" curriculum of education.

The often newly, and if not newly, often more insistently self-aware constituent peoples living within the Hungarian aspect of the apparently failing Habsburg system of monarchy tended to strongly aspire to live in future, (should the Habsburg authority actually fall), under the political sovereignty of their own "self-accepted" nation rather than that of any "other" nation.

On the 15 March, 1848, constitutional deliberations had been authorised to take place in relation to the "Austrian" aspect of the Habsburg's realms by an administration faced with pressing popular demands being made in Vienna and other important cities and towns for political liberalisations.

Formal "Habsburg" consent was given to the election of persons who would then meet in order to devise new constitutional arrangements.

One outcome of the turmoils of 1848 was a newly introduced wider voting franchise in relation to this process of election which resulted in an unprecedentedly large number on peasant deputies, (92 out of 383), with very few deputies being aristocrats, and with more than half on the deputies being of Slavic origin. Radicals, (who tended to be German), were outnumbered by a mixed bag of conservatives comprising Polish noblemen, Ruthenian peasants, Czech liberals, Tyrolese clericals and others.

The Habsburg capital, Vienna, became locally enthused by "German National Liberal" ideology identifying with the establishment of a constitutional "German" state. Some socialistic radicalism was played out in the streets and made claims upon the public purse.

In late May, 1848, the Habsburg emperor and his family departed clandestinely from his turbulent capital.

Concerns about possible future Russian or Germanic encroachments upon "Habsburg" Slavic Europe greatly contributed to the emergence of a co-operative and mutually linguistically accommodating "Austro-Slavism" amongst the Slavic subjects of the apparently failing Habsburg Monarchy with a view of maintaining that monarchy as something of a mutually defensive umbrella under which diverse peoples could live and enjoy some linguistic freedoms.

An historically significant Pan-Slav Congress was held in Prague in early June, 1848, where such "Austro-Slavism" was endorsed by representatives drawn from across the Habsburg monarchy's Slavic lands.

During the deliberations of this Pan-Slav Congress Czechs and Slovaks together with Poles and Ruthenes from within the long accepted "Austrian" aspect of the Habsburg realms were joined by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs despite an Habsburg adminstrative ruling that seemed to newly place their homelands explicitly under the political competence of the Hungarian Diet.

As the weeks passed many of the Slavic representatives participating in the constitutional deliberations felt uncomfortable in generally "German National Liberal" supporting Vienna.

Due to a steep fall off in trade many persons came to be maintained at public expense on work schemes that were seen by their detractors as being unproductive and as open to abuse. Such perceived social radicalism alarmed many conservatives.

Things settled down, however, such that the Emperor felt able to respond positively to entreaties that he return to his capital city.

There was a particularly serious episode of political insurgency in Vienna in early October following on from the proposed deployment of military forces against those then holding the reins of power in the would-be "constitutional", but tragically ethnically divided, kingdom of Hungary.

This insurgency was perpetrated by radical elements favouring association with the wider body of German states and constitutional liberties who could see a humbling, by the Habsburg authority, of those then holding the reins of power in the Hungarian kingdom as being a potential key stepping stone to a full recovery of power by the Habsburg system and the likely suppression of their own agendas for constitutional governance in Vienna and for some form of association with a "Germanic National Liberal" future.

The Emperor again departed from Vienna and authorised a relocation of the constitutional deliberations intended to provide an outcome for the "Austrian" aspect of his realms from Vienna to Kremisier; a town lying not too far distant from his own place of refuge at Olomouc in the Moravian provinces.

In the absence of the many Germanically, or radically, inclined representatives who remained in Vienna at this time, the debates held at Kremsier were even more evidently dominated by Slavic representives who hoped to make constitutional arrangement for the establishment the programme of "Austro-Slavism" outlined at the Prague Pan-Slav Congress than they had been during the constitutional deliberations held in Vienna itself.

Constitutional, liberal and national "movement" seemed to be on the point of winning dramatic changes for several months in 1848 and into 1849.

Within the historic states of Germany a more politically united and constitutional future for the German peoples was being proposed in a parliamentary setting in Frankfurt.

Within the Italian peninsula the King of Piedmont-Sardinia openly defied the weakened Habsburg authority by championing a limitedly constitutional, monarchist, future for most of the northern Italian peninsula whilst the historic states of the church were transformed into a Roman Republic by a locally triumphant Italian Republicanism which had apirations towards a thoroughly constitutional, republican, future for the entirety of the Italian peninsula holding that "the Roman Republic will enter into such relations with the rest of Italy as our common nationality demands".

Events unfolded in such a way that perceived social radicalism alienated powerful sections of the population and appalling inter-ethnic rivalries broke out allowing support to grow for the re-establishment of "order".

A re-establishment of Habsburg power and the conservatively inclined Tsar of Russia, (who was seriously alarmed at the possible implications that a break-up of the Habsburg Monarchy might have for his own Empire and its very diverse peoples and territories), also contributed to a recovery of traditional "order".

Most of western and southern Europe came to be ruled, as before, by emperors and kings. In the case of France where an unpopular king had been deposed and monarchy was held "to be abolished without possibility of return", many powers were vested in one Louis Napoleon ~ a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte ~ who had stood for election promising to follow conservative policies and had been elected President of the newly established "second" French Republic.

By late 1849 most of Europe had been superficially returned politically and socially to practices that had been in place before the onset of the spate of revolutionism just outlined.

Nevertheless, when in February, 1948, the historian Lewis Namier delivered a lecture commemorating the centennial of the European Revolutions of 1848 his presentation included the conclusion that:-

"1848

remains a seed-plot of history. It crystallized ideas and projected the pattern of

things to come; it determined the course of the following century".

Over several decades subsequent to the events of 1848 the Dynastic Europe of sovereign Emperors and Kings was consistently gradually eroded, and

occasionally violently shaken apart, by the forces of constitutionalism, liberalism, democracy, nationalism and

socialism.The Europe of sovereign Emperors and Kings was eventually undermined to the degree that it was very largely replaced by a number of political entities ~ constitutional monarchies as well as constitutional republics ~ wherein constitutionalism, liberalism and democracy have established places, wherein (relatively socialistic) leftist and (relatively capitalistic) rightist political parties compete for power, wherein many nationalist and linguistic aspirations are pursued, where some efforts have been made to provide for the accommodation of cultural or linguistic minorities and where environmental concerns have come to the fore.

(i.e., id est, that is) ~ Modern Europe.

Learning practically useful lessons ~

of Human History

Our pages will now turn towards a consideration of how far can actually hope to learn lessons from history by

showing something of how and why dramatic socio-political change can

happen - (this will, of course, demand an acceptance that human history has not been all sweetness and light!!!)

Wisdom about why turbulent episodes have happened may hopefully lead to the development of policies which tend to provide settlement to current turmoils and to the inhibition of future turmoils.

Popular European History pages on this site

The European Revolutions of 1848

Italian Unification - Cavour, Garibaldi and the Unification of Risorgimento Italy

Otto von Bismarck & The wars of German unification

First World War ~ Diplomacy : The ideas of Woodrow Wilson and Lenin

Italian Unification - Cavour, Garibaldi and the Unification of Risorgimento Italy

Otto von Bismarck & The wars of German unification

First World War ~ Diplomacy : The ideas of Woodrow Wilson and Lenin

Emerson wrote these lines towards the end of his essay, History :-

"every history should be written in a wisdom which divined the range of our affinities and looked at facts as symbols. I am ashamed to see what a shallow village tale our so-called History is".

and actually concluded the essay with this paragraph:-

"Broader and deeper we must write our annals, - from an ethical reformation, from an influx of the ever new, ever sanative conscience, - if we would trulier express our central and wide-related nature, instead of this old chronology of selfishness and pride to which we have too long lent our eyes. Already that day exists for us, shines in on us at unawares, but the path of science and of letters is not the way into nature. The idiot, the Indian, the child, and unschooled farmer's boy, stand nearer to the light by which nature is to be read, than the dissector or the antiquary.

We particularly recommend our series of pages that consider The European Revolutions of 1848 as tending

to display the action of Human Affinities in the shaping of

events.

"every history should be written in a wisdom which divined the range of our affinities and looked at facts as symbols. I am ashamed to see what a shallow village tale our so-called History is".

and actually concluded the essay with this paragraph:-

"Broader and deeper we must write our annals, - from an ethical reformation, from an influx of the ever new, ever sanative conscience, - if we would trulier express our central and wide-related nature, instead of this old chronology of selfishness and pride to which we have too long lent our eyes. Already that day exists for us, shines in on us at unawares, but the path of science and of letters is not the way into nature. The idiot, the Indian, the child, and unschooled farmer's boy, stand nearer to the light by which nature is to be read, than the dissector or the antiquary.