Sarah Parcak was born and grew up in Bangor, Maine.

She graduated from Bangor High School in 1997. Her personal inclinations and abilities, together with opportunities she had for gaining a good education, led to her gaining a bachelor degree in Egyptology and Archaeological Studies from Yale University in 2001.

She subsequently gained masters and doctoral degrees from Cambridge University, England.

She had been a stand-out soccer player at Bangor High and, whilst at Cambridge, significantly helped their team to beat arch-rivals Oxford with two goals and two assists to her credit on the day.

She worked for a time at the University of Wales, Swansea, lecturing in Egyptian art and history before gaining an assistant professorship in Anthropology at the University of Alabama.

From Egyptology to satellite archaeology from space

She had managed to secure a place at Yale University with the intention of studying Archaeology but without any initial firm intention as to an eventual specialism.

The week before classes started, an Archaeology professor named William Kelly Simpson invited all first-years at Yale's Timothy Dwight college to take a bus to Katonah, N.Y. and see his estate. He had an incredibly beautiful home situated in extensive grounds, where there was ample room for the freshmen students to picnic and get to know each other before the semester began.

Whilst on the journey to Katonah the name William Kelly Simpson seemed, to Sarah Parcak, to be one she had heard before and it came to her that she had heard of him as being a very famous Egyptologist. On the day of the visit Simpson invited the visiting freshmen to see inside his home, Sarah Parcak was the only one to accept the offer.

Simpson was the husband of a granddaughter of the immensely rich finacier John D. Rockefeller, and had become a world-renowned art collector, decorating the rooms of their home with antiques and the walls with some significant works by famous French Impressionist artists.

Whilst proceeding from room to room Sarah Parcak found herself in Simpson's office which was lined ceiling-high, and it was a high ceiling, with Egyptology books. Fascinated by the ambience of the room she seems, there and then, to have more or less decided:-

"That's it. I'm done. I want to be an Egyptologist."

How then to explain her emergence as a celebrated Space Archaeologist and practicioner of satellite archaeology from space?

When she and her brother were growing up their grandfather - a retired forestry professor at the University of Maine and one of the pioneers of aerial photography being applied to achieve better practices in forestry - would take them to his office at the engineering firm where he worked.

Sarah Parcak has said of this experience:-

"He had his aerial photographic equipment there, including a stereoscope, [with which] you can place two aerial photos on top of each other and view them in 3D."

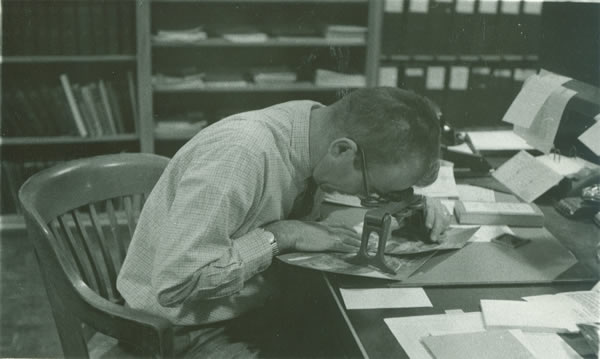

Sarah Parcak's grandfather Dr. Harold Young using a stereoscope

Largely inspired by the example of her grandfather she opted to take a course in satellite imaging and its interpretation whilst at Yale. She embarked on this course, entitled "Observing Earth from Space", at the start of her senior year.

She actually took this course somewhat impulsively and against the advice of teaching staff there who believed her to probably have an insufficiently strong grounding in physics to be able to cope with its demanding content.

She seems to have genuinely struggled, and to have been awarded at an "F" marking on her mid-term paper ~ this "F" grading being the first she had ever received during her years of education. She became seriously concerned lest her poor performance on the course would lower her overall grade average and thus her ability to qualify herself for the further courses of study she hoped to undertake.

Some kindly soul, however, decided to help her and showed her, over an hour or so of demonstrative tutorial, how to sufficiently cope with the many technicalities of manipulating and interpreting satellite imagery such that her eventual grading on the course turned out to be a "B".

That kindly soul seems to remain as a friend today.

The insight she had received into the potential power of satellite imagery interpretation made a profound impression on Sarah Parcak and left her enthusiastic about making efforts to apply that potential power in her future archaeological studies.

During her years of postgraduate study to masters, and then to doctoral level, at Cambridge University she utilised the interpretation of imagery derived from satellite remote sensing as a principal theme of her studies.

In the interview process which resulted in her appointment to an assistant professorship at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, she seems to have actually proposed the establishment of a dedicated satellite remote sensing lab there. She subsequently contributed significantly to the setting-up of such a lab: the project has enjoyed considerable success and has led to the foundation of a Laboratory for Global Observation at the University of Alabama. Sarah Parcak serves as its director.

Her roles in the founding and subsequent directing of this facilty, together with the sometimes pretty awesome results which have been gained through its operation, have allowed Dr Sarah Parcak to be regarded as a world-leading practioner of Space Archaeology techniques.

Satellite remote sensing

The Arts and the Arts and the Sciences are the Sciences ~ an interfacing between satellite technology and archaeological studies was surely "on the horizon" but also hard to fully anticipate or provide for in the training up of archaeological professionals.When she was at Cambridge Sarah Parcak searched papers in geology and other fields for information on how to analyze satellite images; there was then no established textbook covering the application of satellite sensing capabilities to archaeology.

Sarah Parcak later proved herself to be capable of literally "writing the book" on the subject. Her 'Satellite Remote Sensing for Archaeology' (2009) becoming regarded as a standard work at the time of its publication.

That being said the capabilities of man-made space satellites, and the methodology that can be applied through their use has been rapidly improving over the years.

Near Infrared and other techniques can remote sense subtle differences in underlying humidities in soils, in densities of materials lying underneath soil surfaces, and differences in plant health: such differences can be highly indicative of their being underlying features which justify archaeological investigation.

Such indication of areas of particular interest has proven to be vital in bringing about many highly significant new findings.

Prior to the viability of Space Archaeology, or satellite archaeology from space, hitherto traditional methods had often proved unable to detect such areas of interest buried as they often could be under apparently featureless terrain or vegetation.

"Buried archaeological remains affect the overlying vegetation, soils and even water in different ways, depending on the landscapes you're examining."

Sarah Parcak

"I'm a space archaeologist. Let me repeat that - I am a space archaeologist. This means that I use satellite images and process them using algorithms and look at subtle differences in the light spectrum that indicate buried things under the ground that I get to go excavate and survey. By the way, NASA has a space archaeology program, so it's a real job."

From a TED radio interview featuring Sarah Parcak.

"The biggest problem we have when looking at satellite imagery is not the processing," she says. "The hardest part is actually eye fatigue. … Imagine hours and hours looking at satellite imagery. We miss things."

Sarah Parcak

"I'm a space archaeologist. Let me repeat that - I am a space archaeologist. This means that I use satellite images and process them using algorithms and look at subtle differences in the light spectrum that indicate buried things under the ground that I get to go excavate and survey. By the way, NASA has a space archaeology program, so it's a real job."

From a TED radio interview featuring Sarah Parcak.

"The biggest problem we have when looking at satellite imagery is not the processing," she says. "The hardest part is actually eye fatigue. … Imagine hours and hours looking at satellite imagery. We miss things."

Sarah Parcak, Space Archaeologist -- PART 1 from THE NEXT LIST on Vimeo.

Documentaries

Chance, it is said, favors the prepared mind.Sarah Parcak's archaeological training, her understanding of space satellite archaeology and improvements in satelite technologies and their have all allowed her to emerge as a leading exponent of satellite remote sensing space archaeology ~ leading to many pretty astonishing discoveries being made by Dr. Parcak and many associated highly-qualified colleagues as they have worked in close co-operation.

Absorbing documentaries covering important discoveries made by the utilisation of archaeology from space techniques with which Sarah Parcak has a an high degree of involvement have come to be broadcast and / or sponsored by many high-profile entities such as the BBC, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, PBS, NOVA/WGBH Boston and France Television.

Egypt's lost Cities (2011) - with which the BBC and the Discovery Channel were significantly involved - covered the finding of 17 possible pyramids, 1000 possible tombs and 3,000 ancient settlements in Egypt.

Rome's Lost Empire (2012) - which again had significant BBC and Discovery Channel involvement - featured findings about many Roman sites in such diverse places as Romania and Tunisia as well as Italy itself.

The research findings seemed to indicate the presence of an unanticipated canal which, if proven to have existed, has the potential to greatly explain how the immense difficulties of transportation between Rome and the nearby seaport of Portus could have been overcome.

A bustling port town such as Portus is accepted as having been would pretty much inevitably had to have had a focus of popular entertainment: but such an arena was notably missing from discovery.

The presence of the foundations of such an arena or amphitheater, where gladiatorial and other spectacles could have been staged, was also indicated in satellite remote sensing findings that became available due to the efforts of Sarah Parcak and her colleagues.

Viking's Unearthed (2016) - a BBC co-production with PBS, NOVA/WGBH Boston and France Television - offered an overview of discoveries at Point Rosee, Newfoundland, which were, for a time, confidently said to have found the second known pre-Columbian example of iron smelting in the New World. The research findings seem to similarly indicate that a second example of Norse or Viking settlement in North America also existed there. Sarah Parcak nevertheless insists, as of April, 2016, that Point Rosee remains possible, rather than proven, as a Viking or Norse settlement.

Sarah Parcak seems to have been reluctant to undertake these latter Viking related studies when they were suggested to her by the BBC. She seems to have been disinclined to voluntarily associate herself with what had, rightly or wrongly since the initial discovery of a Norse or Viking site in northern Newfoundland in 1960, come to be regarded as a pursuit freely engaged in moreso by "amateurs" and "mavericks" than by serious archaeologists.

In a subsequent Yale lecture she portrayed her attitude at the time as being one of - "I don't want to be one of these crazy people."

She eventually allowed herself to be persuaded to undertake these studies - financed by the BBC, National Geographic and others - whilst apparently having no real personal expectation that anything worthwhile was likely be discovered.

Sarah Parcak has become celebrated as a practioner of satellite archaeology from space, she nevertheless seems to fully accept that her best claims to scholarly authority, as an archaeologist, lie in the field of Egyptology. Her own personal inclination to assume that the likelyhood of there being worthwhile findings in relation to viking activity was extremely low was reinforced by the similarly skeptical opinion she received from leading experts in the area of "the Vikings presence in North America."

The findings from this hesitantly embarked upon Vikings-related Space Archaeology project can thus be said to have greatly exceeded her expectations!